To that end, this article will help you identify poison ivy in its various stages, and provide some information about why we react, what to do if you have skin exposure, and how to eliminate it from your yard and garden!

"Leaves of three, let it be"

Poison ivy is among the most widely recognized of a trio of three related plants: poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. As a camp counselor back in the late 1980's and early 1990's, I taught the campers the familiar saying, "Leaves of three, let it be!" When in doubt, it was better for them to avoid touching a harmless plant, if they were unsure of the identification, than for them to suffer from the effects of one of these toxic plants. I have been very fortunate thus far, as I have never had a reaction, even though I know I have been repeatedly exposed to poison ivy. I never take for granted that I will not have a reaction in the future, however. Your sensitivity to the toxins in poison ivy increase with each exposure, so even those who have not previously reacted are still in danger of breaking out with each new exposure. Those who have previously reacted need to be even more careful, as often each reaction is worse than the one before it!

You are never far from poison ivy. It's everywhere.

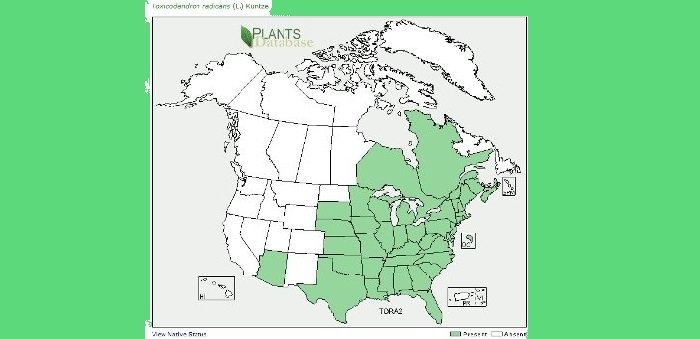

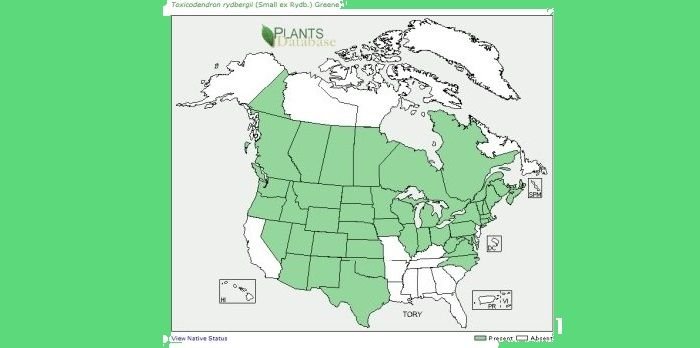

Perhaps it is so widely recognized because it has one of the widest ranges of naturalization in the United States , Canada, and Mexico. These maps, provided by the United States Department of Agriculture, illustrate just how widely spread poison ivy is in the United States and Canada. The first shows naturalized instances of Western Poison Ivy, Toxicodendron rydbergii, while the second shows Eastern Poison Ivy, Toxicodendron radicans. Together, they work to bring discomfort and wretchedness to people from coast to coast throughout North America.

How do I recognize poison ivy?

Poison ivy, which is a perennial, has a wide variety of possible growth habits. It may be present as a trailing vine, growing horizontally along the ground on long stems in wooded areas or clearings, or across rocky surfaces. It may grow as an upright herbaceous plant, which is how I most commonly see it in the wooded areas of the midwest. It may grow as a climbing vine, inserting aerial roots along the length of its hairy, fibrous vining stem, and grow up a tree, utility pole, or building. I once saw a poison ivy vine growing nearly 25 feet up the corner of a building on the campus of Illinois State University, in Normal, Illinois. It can even look like deciduous shrub, especially if it is cut back, and then sends up multiple new stems from the surviving rootstock.

The most commonly recognized feature of poison ivy is the trifoliate pattern of the compound leaves, made up of a trio of three leaflets. The two side leaflets grow opposite of each other, and the third grows between them on a stem, or petiole, that is slightly longer than the outer two. The vines of larger, climbing plants are often hairy and ropey looking. Stems are often reddish in color, though the primary vine can be green or brown, depending on the age of the plant and the season. Immature leaves are often reddish when they first appear, turning green and sometimes slightly shiny as they mature. In the fall, they turn golden orange or red, and are often the first leaves to turn color, which makes them easier to identify.

Different forms of poison ivy have slightly different appearances to the leaves. In particular, the lobes, or "toothing" on the edges of the leaves varies from one geographic area of the country to another. In our area, the most common variety has lobed edges on both sides of the center leaf, and lobed edges on only the outer edges of the two outer leaves. The inner edges of the side leaves are relatively smooth. I taught my children to recognize it this way: the center leaf looks like a mitten with thumbs on both sides, and the outer leaves look like mittens with thumbs on the outer edges only. They posed for a picture to try to illustrate this concept. The layered hands in the center represent the center leaf, with "thumbs" or serrated edges on both sides of the leaf, while the two outer hands represent the outer two leaves, with smooth edges on the sides nearest the center leaf, and "thumbs," or serrated edges, on the outer edges. Compare it to the trio of leaves in the picture of poison ivy to the right.

Unfortunately, this description does not always hold true. Some varieties are more jagged and deeply lobed than others. Some don't have any jagged edges at all, and have an almost heart-shaped leaf. In these cases, you must depend on other identifying factors, such as thornless stems, and the clusters of three leaflets on their own stem, which is an off-shoot of the main vine or stem.

The fruits of poison ivy develop in small clusters of pale, greenish-white, waxy-looking berries. They are roughly the size of currents. Each berry contains a single seed. The fruits are often eaten by birds and other wildlife, who then spread the seeds to new areas through their droppings.

So why do we react to poison ivy, anyway?

The short answer is that the plant has developed a very effective defense system. Every part of the plant, including the stems, leaves, flowers, roots, and berries, produce a nonvolatile oily substance known as urushiol. This compound is clear and usually not visible, either on the plant or on the skin, clothing, or the fur of animals. This protective sap binds to the skin of unwary hikers and gardeners, causing a miserable allergic reaction called contact dermatitis in the majority of the people who come into contact with it. Exposure on the hands is particularly dangerous, as many people touch numerous parts of their body with their hands before they realize they have the poison ivy sap on their hands. Contact with the eyes can be particularly painful and dangerous, even causing the eyes to swell completely shut.

Symptoms may begin with severe itching, inflammation, reddening of the skin, and raised bumps that become blisters. Those with extreme sensitivity may even experience anaphylaxis, or potentially fatal swelling of the airways, and require hospitalization. Contrary to popular belief, the fluid from the blisters does not cause the poison ivy rash to spread. A more likely explanation for a second wave of rash and blistering is that some areas of the body had more concentrated exposure, causing more immediate reactions, while areas that have less urushiol sap on them reacted more slowly. Another possibility is that secondary exposure occurred from handling clothing, shoes, or the fur of pets that also carry the poison ivy sap.

You cannot get poison ivy from contact with another person who is suffering from a reaction to it, unless they have not washed the area and still have the sap on their skin. It IS possible, however, for someone to scratch their own poison ivy lesions to the point of causing themselves a secondary infection from bacteria introduced through the open wounds from their fingernails.

If the rash does not improve within a few days, worsens or spreads to more than 1/4 of your skin area, or shows signs of infection (pus, yellow discharge or scabs, warm to the touch, or causes a fever), you may need to see a doctor for more intensive treatment, such as prednisone or other steroids to reduce swelling and inflammation.

If you have a known sensitivity to poison ivy, it may be advisable to avoid several edibles that are in the same family, such as cashew and pistachio nuts, and mangoes. All three can cause allergic reactions in those with poison ivy allergies. The reactions to these foods may be more severe during an episode of poison ivy rashes, even if you have never previously had a reaction to those foods.

What to do if you've been exposed

The first thing you should do is wash the affected area thoroughly and repeatedly, with soap and COLD water. Warm water can spread the sap over a larger area of skin, and also hastens its absorption into your skin. Taking a warm bath could be disastrous, as the oils would float on the water, and then be redistributed over all of your exposed skin. Timely removal is critical, it absorbs into the skin within 10 minutes. Once it has penetrated the surface of the skin, the allergic reaction begins. The University of Oklahoma website recommends using dishwashing liquid or lye soap, rather than standard hand soap, as the degreasing agents help to neutralize the oily sap. [1] My husband swears by the effectiveness of Fels Naptha soap, which is available locally at both our pharmacy and the farmer supply store. You can also cleanse areas known to be exposed to poison ivy with rubbing alcohol, preferably poured over the area, rather than wiped on, to help cut the oils and remove them from your skin. Any wiping or scrubbing action can spread the urushiol oils across more skin surface, increasing the size of the corresponding rash.

Common over-the-counter treatments for poison ivy lesions are Calamine lotion, oatmeal baths, and baking soda pastes. There are some soaps and lotions marketed specifically for the removal and treatment of poison ivy, though I am not personally familiar with them , and can't comment on their effectiveness.

The most common botanical folk remedy for poison ivy is the application of jewelweed, which is a wild variety of impatiens. They are reportedly often found growing near established clumps of poison ivy. Various applications include peeling the stems and applying the juice directly to the lesions, or brewing the crushed leaves and stems into a strong infusion, which is applied topically. As with any home remedy, I would recommend caution, and experimenting with a very small exposure, as it is possible to develop a severe allergic reaction to jewelweed, as well! Absolutely do not take jewelweed internally, as it can cause severe gastric discomfort.

If your dog or other pet has gotten into poison ivy, it is unlikely that your pet will develop a reaction. Humans seem to be much more susceptible. Dogs may carry the oils on their coat, however, spreading it through your house and causing reactions in anyone who pets them. If you know your pet has gotten into poison ivy, bathe them thoroughly with your preferred pet shampoo. Wear rubber gloves and protect your skin from exposure. If possible, wash them outside, so you don't transfer the oils to your bathtub. If you do bathe them inside, clean your bathtub thoroughly and rinse repeatedly before you use it yourself!

It is also critically important to thoroughly and repeatedly wash any clothing that you were wearing when you were exposed in a separate load from other clothing. If you are dangerously allergic to poison ivy, and concerned about re-exposure from handling the affected clothing, bag the clothing in plastic and discard it entirely.

How do I remove poison ivy from my garden or yard?

You basically only have two alternatives: physically remove it by hand, or employ strong chemicals to kill the plant. Both alternatives have their dangers, however, and require extreme caution. If you are removing poison ivy by hand, be sure that you have on long pants and long sleeves and gloves. If possible, buy an inexpensive plastic rain suit that can be bagged and discarded after use. Cover as much skin as possible, and try to remove the clothing without touching any exterior surfaces with your hands or skin.

Even if you think it's dead, it probably isn't

Poison ivy, when deeply entrenched, can be very difficult to dig up and remove, as vines lying on the ground can send out adventitious roots, and can also spread by runners underground. Under no circumstances should you mow over a patch of poison ivy or attack it with a weed-eater, as this will spread the chopped up bits over a wide area. Even dead, brown leaves can cause contact dermatitis! You can, however, repeatedly cut it back to ground level, as without leaves to produce chlorophyll, it will eventually "starve" the roots. Heavy mulching, to the extent that all light is excluded, is also sometimes effective, though the dead plants are still a risk factor. All poison ivy parts should be bagged and disposed of in the trash. Do NOT under any circumstances burn refuse that contains poison ivy, as urushiol is contained in the smoke, and can be inhaled. This can cause a potentially deadly internal reaction in the lungs, with swelling of the airways leading to difficulty in breathing, in addition to the danger of getting urushiol on your exposed skin from the smoke. For this reason, you should also NOT bag it up in the brown lawn waste bags for pick-up by your local municipality. The contents of those bags are often burned or composted, both of which could be disastrous for unsuspecting people who might come into contact with the plant matter or breathe the smoke from the burned refuse.

There are several herbicides labeled for use on poison ivy. Their use requires caution, however, as they will also kill desirable plants in your garden beds.

One common herbicide is glyphosphate, which can be found in preparations such as Roundup Poison Ivy or Kleenup. This may take repeated applications, as sprouts may re-emerge from the roots . Depending on the brand, it may be sold as a liquid spray, a liquid to brush onto selected plants, or a foam. If the poison ivy is near plants that you want to keep, or climbing a tree, try painting it on the surface of the ivy with a paintbrush. It works through absorption through the leaves, and may take a week or more to thoroughly spread through the entire plant. Glyphosphate does not remain in the soil. It is a non-selective herbicide, however, and will kill most plants and grasses it contacts.

Amitrole is similar to glyphosphate, in that it is absorbed through the leaves; however, it does remain in the soil for a period of several weeks, and should not be used where food crops will be grown, or where animals will graze. [2]

Another common herbicide used for poison ivy is triclopyr, such as Ortho Brush-B-Gone, Garlon, and Redeem. This is a very strong chemical, so be very cautious not to get any on your skin, and read the label carefully. This herbicide does leave a residue in the soil which can be harmful over a longer period, though it doesn't have any detrimental effect on grasses. It is specifically a broadleaf herbicide, which makes it safer to use around lawns and ornamental grasses. It is particularly damaging to trees, so this would not be a good application for a vining ivy on a tree.

With any chemical treatment, be sure to choose a relatively windless day, to avoid causing drift to other areas of your yard. Since they are applied topically, watch the forecast a choose a day with no rain predicted in the next 24-48 hours. Ideally, apply herbicides when the plants are in a season of rapid growth, and before they flower and set fruit.

There are non-glyposphate options that are safer for the environment and your family.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commissions at no cost to you

References and general information:

[1], [2] http://www.ou.edu/oupd/pivyp.htm

http://extension.missouri.edu/p/G4880

http://poisonivy.aesir.com/view/control.html

Photo credits:

Maps of poison ivy distribution: From United States Department of Agriculture. In public domain.

Hands demonstrating lobes of poison ivy leaves: Angela Carson. All rights reserved

Poison ivy rash: via Flickr Creative Commons, by jovino. Some rights reserved.

All other images courtesy of PlantFiles