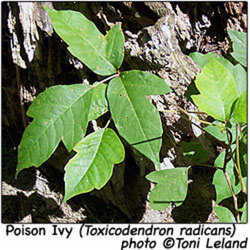

This article is the second in a three part series about poison ivy, poison sumac, and poison oak, all of which are flowering plants in the Toxicodendron genus of the sumac family, Anacardiaceae. The first article in the series, on poison ivy, can be found here.

Here in Illinois, the roadsides and hilltops are a-blaze with color. Among my favorites in the autumn are the brilliant, toothy leaves of the staghorn sumac tree. I've often hiked trails and examined the compound leaves and their spiky flower heads up close. Fortunately, the sumac that grows in our area is primarily Rhus typhina, one of many harmless varieties.

There is, however, a sumac that should be avoided at all costs: Toxicodendron vernix, better known as poison sumac. Poison sumac is one of a trio of plants (poison ivy, poison sumac, and poison oak) that produce an oil called urushiol, which is a potent allergen. The vast majority of people (estimates range from 60-90%, depending on your source) react to contact with urushiol by developing a distinctive allergic rash with oozing blisters.

Poison sumac can take the form of either a small bush or a woody shrub, and can range in size from 9 to 20 feet tall. Its potential range reaches from USDA zone 3a to 8b. The USDA Plant Database gives a much wider range of distribution (left) than the US Geological Survey (right), but both agree that it is most commonly found in the eastern and southern quadrants of the United States.

|  |

Map of Poison Sumac distribution, US Department of Agriculture | Map of Poison Sumac distribution, US Geological Survey |

So, how do you know if a sumac in your area is the poisonous variety, or one of the harmless species?

Where is it growing?

Poison sumac, (Toxicodendron vernix or Rhus vernix) is typically found in very wet areas. It often grows in swamps, bogs, or wetlands, sometimes with the roots and lower stems completely submerged. They have a fairly limited range of growth, limited mostly to the eastern 1/3 of the country, as illustrated in the maps above.

In contrast, most other species of sumac prefer dry areas with well-drained soil. They can be found in wooded areas, along fencerows, and along roadsides throughout the entire United States, and much of Canada.

What color are the berries?

The best time to identify the fruits of the trees is in the autumn, when the berries are ripe.

The berries of poison sumac are white or pale green, grow at the base of the leaves and hang downward from the stems, somewhat like a cluster of grapes.

The most common non-poisonous sumac, staghorn sumac, bears bright orange or red berries which grow at the ends of the stems, and they are held upright on the stems.

Winged Sumac, Rhus copallina, also bears dark red berries in an upright formation.

What do the stems and the edges of the leaves look like?

The stems of poison sumac are smooth and hairless, as are the leaves.

|  |

Poison Sumac, Summer Colors, with flowers | Poison Sumac, Autumn Color |

The stems of most non-poisonous varieties are rough and hairy, though there are some non-poisonous varieties with smoother leaves and stems, such as smooth sumac and winged sumac. The leaves vary widely by species, but most are hairy and have toothed or finely cut leaves. Some, such as the Tiger Eye Sumac pictured below, even resemble the lacy leaves of a Japanese maple tree.

|  |

Deeply cut foliage of Tiger's Eye Staghorn Sumac, | Staghorn Sumac, Autumn Colors |

|  |

Winged Sumac, Autumn Colors | Staghorn Sumac Stems |

Why is it so dangerous?

Poison sumac is far more potent than either poison oak or poison ivy, and is sometimes identified as the most toxic plant species in the United States. [1] Thankfully, it is the least common of the three, and you are unlikely to come into contact with it unless you spend time in swamps and wetlands.

It takes very little of the urushiol oil to cause a horrible reaction, and every time you are exposed, your potential for a reaction increases. Even people who initially have no reaction to contact with urushiol, from any of the plants in this family, can become increasingly sensitized. People who do react tend to have increasingly severe reactions with each exposure, which makes it all the more important to avoid contact with urushiol-producing plants.

There is a connection between allergic reactions to poison ivy, oak,and sumac, and food allergies to other plants in this family, which include cashew nuts, pistachios, and mangoes, among others. If you have a known food allergy to any of these foods, be particularly cautious around poison sumac! Likewise, even if you have never previously reacted to any of those nuts or fruits, you may want to avoid consuming them if you have been exposed to any of the urushiol-producing plants. There are anecdotal accounts of people having severe reactions to the foods after being sensitized by a poison ivy or other urushiol-provoked rash.

One reason the plant is so dangerous is that every part of the plant produces the oils, and they remain active for as long as 5 years, even after the plant is dead. You can contract the rash from the bare stems in the winter, from contacting the roots while digging, or from handling dead and dry leaves. It is especially dangerous to burn any part of this plant, as the oil vaporizes when hot and is distributed in the smoke. Inhaling the airborne particles in the smoke can cause a potentially fatal reaction inside the lungs, or a widespread rash over any exposed skin that the smoke drifts across.

What do I do if I've been exposed?

Just like with poison ivy, it is critical to remove the urushiol oil from your skin as soon as possible. Urushiol is absorbed into the skin within 10 minutes of contact, so it is important to wash any exposed parts thoroughly after suspected or known contact. It may take 12 hours or more for the rash to appear, especially on your first exposure, so don't wait for a reaction to take action!

It is best to use cool water and soap to wash the oils from your skin, as warm water can cause the oil to spread over a larger area. Hot water also opens the pores of the skin, allowing for faster penetration into the skin. Fels naptha soap is often effective at removing the oils thoroughly, as is dish detergent, due to its grease-cutting properties. Another cleanser recommended by the Forestry Service for urushiol removal is called TECNU. It can even be used on leather shoes and porous surfaces. Rubbing alcohol can also help dissolve the oils, though you must be careful not to wipe the area, as this can spread the oils. Even if you wash promptly, you may still experience a rash, but with less severity or a shorter duration.

If you do develop a rash, there are many over-the-counter remedies to help alleviate the symptoms. Creams and lotions that dry up the rash, such as calamine lotion and hydrocortisone creams, are commonly used. Cool baths with baking soda, oatmeal, or colloidal baths can provide some relief, as can some topical anesthetics like menthol, benzocaine, and pramoxine, which numb the area temporarily. Oral antihistmines, such as Benadryl, offer some relief, but can make you drowsy.

If the itchiness of the rash is driving you to distraction, there is anecdotal evidence that taking a bath or shower in water as hot as you can stand it, or applying hot compresses to the areas with the worst itching, can give up to several hours of relief. [2] It is important that you only do this after all urushiol oils have been removed from the skin, and be careful not to scald the skin, which would further injure it and slow the healing process. This works by releasing the histamines that build up in the skin from the body's allergic response to the urushiol oils.

If your rash develops much more quickly, with onset in 4-12 hours instead of 24-48 hours, or if your eyes swell shut or you experience difficulty breathing, you should seek medical attention immediately. Some severe reactions require prescription medications, such as steroids to reduce inflammation, or even hospitalization.

How do I control or remove poison sumac?

First, be sure of your identification before you remove the sumac shrubs in question. There is no reason to put forth the expense and effort if you have a stand of staghorn sumac, rather than the toxicodendron variety. If you are certain that it IS poison sumac, and that removal is necessary, be sure to wear long pants, long sleeves, gloves, and boots, covering as much skin as possible. If you have the option of wearing a disposable coverall outfit, that is even better. While you can attempt to control poison sumac at any time of year, you will have the best results if you treat it in May through July while the plants are flowering. [3]

The recommended method of control is to use an herbicide, such as glyphosate (Roundup, Kleenup), which is absorbed through the leaves of the plant. It is a non-selective herbicide, so be careful not to overspray onto plants you want to keep. You can cut the plant back to a foot or so above ground level and apply glyphosate immediately. Poison sumac, like the other plants in this family, are persistent, so repeated applications may be necessary to completely kill the plant. Watch carefully for resprouting or distribution by wildlife, and treat while the seedlings are young. Be very careful how you dispose of any plant matter. Again, do not burn any leaves or woody stems. Bag them and dispose of them in the trash, rather than putting them in landscape waste bags that may be picked up and burned by unsuspecting municipal workers.

Wash any clothes worn while working near poison sumac separately and repeatedly. Tools should be cleaned with rubbing alcohol, to avoid repeated exposure to urushiol oil.

Related links:

Skin Rash Hall of Fame. Some pictures are graphic, so proceed with caution if you have a weak stomach!

References:

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poison_sumac

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urushiol-induced_contact_dermatitis, http://www.poisonivyremoval.com/ordereze/content/8/summary.aspx

[3] http://www.tdi.texas.gov/pubs/videoresource/fspoisonivyoaks.pdf

Photo Credits, in order of appearance:

(Click on any image to see the original full-sized picture.)

Thumbnail picture at top of article: From Wikimedia Commons, public domain, by Robert H. Mohlenbrock. Original entry here.

USDA Map, from the Plants Database. Public Domain.

US Geological Survey Map, from Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Poison Sumac with berries: from Flickr Creative Commons, posted by ornitholoco. Credited to Andy Jones, Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Some rights reserved.

Close-up of Staghorn Sumac berries: Flickr Creative Commons, by Martin LaBar. Some rights reserved.

Winged Sumac berries: from Flickr Creative Commons, by Katja Schulz (treegrow). Some rights reserved.

Poison Sumac, summer colors: from Flickr Creative Commons, by Jennifer Jordan (lovingshiva). Some rights reserved.

Poison Sumac, autumn colors: from Flickr Creative Commons, by elizawbarrett. Some rights reserved.

Tiger Eye Sumac, by Angela Carson. All rights reserved.

Staghorn Sumac, autumn color: from Flickr Creative Commons, by SimonDeanMedia. Some rights reserved.

Winged Sumac, from PlantFiles, by DG member Melody Rose (Melody). All rights reserved.

Sumac Stems, from Flickr Creative Commons, by Hadleygrass is asparagus. Some rights reserved.