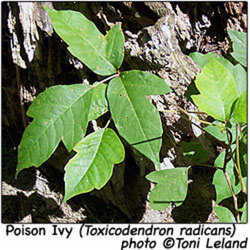

As a resident of the midwest, I don't have much first-hand experience with Poison oak. In our neck of the woods, poison ivy is the much more common culprit if someone is experiencing a miserable skin reaction after a jaunt in the woods. However, a good friend of mine asked if I knew exactly what the ranges were for poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, and if all three were present in Illinois. That innocent question sent me on a rabbit hunt that has lasted me several months!

There are two primary varieties of poison oak, called Toxicodendron diversilobum, and Toxicodendron pubescens. The two have fairly distinct ranges within North America, with T. diversilobum concentrated mostly in the western region of the United States and Canada (hence the common name Pacific Poison Oak, or Western Poison Oak), and T. pubescens growing primarily in the south-eastern quarter of the United States (lending it the common name Eastern Poison Oak, or Atlantic Poison Oak.) Their ranges do not overlap, according to the distribution maps provided by the United States Department of Agriculture:

| Distribution of Poison Oak in North America | ||

|  | |

Western Poison Oak, | Eastern Poison Oak, T. pubescens | |

One of the primary difficulties in avoiding poison oak, and especially T. diversilobum, is that there is a great diversity in appearance from plant to plant. Easily memorized rhymes, such as "Leaves of three, let it be" don't apply when the plant in question sometimes has 3 leaves, but then again, sometimes has more. The University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources website description illustrates this point:

"Leaves normally consist of three leaflets with the stalk of the central leaflet being longer than those of the other two; however, leaves occasionally are comprised of 5, 7, or 9 leaflets. Leaves of true oaks, which are superficially similar, grow singly, not in groups. Poison oak leaves alternate on the stem. Each leaflet is 1 to 4 inches long and smooth with toothed or somewhat lobed edges. The diversity in leaf size and shape accounts for the Latin term diversilobum in the species name. The surface of the leaves can be glossy or dull and sometimes even somewhat hairy, especially on the lower surface." [1]

T. diversilobum generally grows in the form of a shrub, ranging from 1- 6 feet tall, though it can sometimes take the form of a vining groundcover. It grows in a wide range of habitats, ranging from sea level to 5,000 feet in elevation, and thriving in both full sun areas and shaded woodlands and forests. Like poison ivy, it can develop aerial roots, allowing it to adhere to the trunks of trees in its vining form. This western variety most closely resembles the deeply lobed leaves of the oak tree, from which it borrows its name.

Eastern Poison Oak, or T. pubescens, more closely resembles poison ivy. It generally takes a more vining form, though it can, on occasion, form a shrub up to 3 feet tall. Eastern Poison Oak does tend to have three leaflets, with the outer two directly opposite each other on the stem, and the third extending on a short stem from between them, forming a loosely triangular pattern. Like poison ivy, the central leaflet often has lobes on both edges, while the outer two leaflets often have one smooth edge and one lobed edge. The leaflets are often covered with fine hairs.

Both eastern and western varieties produce insignificant white or pale green blossoms in the spring:

and white or cream berry-like drupes in the summer. The fruits often have a papery husk or outer covering.

|  |

Like its noxious cousins, poison ivy and poison sumac, both varieties of poison oak also produce urushiol, an oily substance that causes severe irritation to the skin of most humans who come into contact with it. All parts of the plants contain urushiol, from the roots, to the stems, leaves, and berries, which makes identification during the winter months particularly important. In the autumn, the leaves turn color, ranging from golds and oranges to brilliant scarlet tones. As difficult as it is to identify the leaves by shape, it becomes even more difficult to identify the plant in late autumn, when the leaves drop from this deciduous plant!

Urushiol begins to penetrate the skin within 10 minutes of contact, though a reaction may not appear until the next day, or even several days later, depending on the degree of exposure. If you think you may have had skin contact with poison oak, you should act immediately to remove as much of the urushiol oil from your skin as possible. If you have access to cool water and soap, especially a detergent-based soap such as dishwashing liquid, that can be a very effective way to cut the oils and remove them from your skin. Avoid using warm or hot water, as that can spread the oils across a wider area of skin, and also open the pores of your skin and hasten the absorption. Fels Naptha soap often recommended by farmers and field workers who come into contact with poison oak or other urushiol-producing plants. There are also commercial soaps marketed specifically for poison ivy, such as Tecnu, that would be equally effective on poison oak, as the compound causing the skin irritation is the same. Be particularly thorough in washing your hands, as a great many people have experienced the misery of spreading urushiol oils to their faces and other tender areas of their body, by touching the affected skin or clothing with their hands, and then touching other areas.

Rubbing alcohol, poured over the affected site immediately after exposure, can also be effective in removing the oils from your skin. As a note of warning, alcohol wipes, frequently found in first aid kits, are NOT a suitable replacement. Any form of wipe will tend to spread the oils across the surface of your skin, rather than removing it.

In addition to promptly washing your skin, you should thoroughly launder any clothing or gloves that you were wearing when exposed, to avoid re-exposure from handing them later. If you had a dog with you on your hike, you should also bathe your pet. Dogs rarely develop an allergic reaction to urushiol themselves, but they can carry the oils on their coat, and spread them to furniture and carpet in your home, upholstery in your car, and to any people who handle them.

If you do experience the uncomfortable, blistering rash that results from contact with urushiol, your first line of treatment will be a combination of over-the-counter preparations. Though nothing will offer rapid or complete relief (the rash generally lasts 10-14 days, or longer for severe reactions), you may find some reduction of itching and pain from the following:

- Oatmeal baths

- Baking Soda pastes

- Calamine Lotion

- Hydrocortisone Cream

- Topical anesthetics like menthol, benzocaine, and pramoxine, which numb the area temporarily.

- Oral antihistmines, such as Benadryl, offer some relief, but can make you drowsy.

- If you are certain the urushiol oils have been thoroughly washed away, using cool water and soap, you can use hot baths or very warm compresses to help relieve the itching temporarily. Just be very careful not to use water that is too hot, or it may scald and further damage your already tender skin, leaving you open to infection.

If your rash is severe, appears unusually rapidly (ie, in 4-6 hours, rather than the usual 24-48 hours after exposure), your eyes swell shut, or you experience any swelling of the mouth or airways or difficulty breathing, seek immediate medical attention. Likewise, if your rash does not begin to improve, is extreme or over a large portion of your body, or is showing signs of infection (pus, milky or cloudy discharge from open blisters, hot to the touch), you may require medical help.

For the first two articles in this series on urushiol-producing plants, see:

Poison Ivy: Identification, Treatment, and Removal

Poison Sumac: How to Identify It, and What to Do If You've Been Exposed

References:

[1] http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7431.html

To view a caption for any photo, hover your mouse over the picture. To see the picture in full size, click on it. All photographs, except the small thumbnail image at the start of the image, will open in a new window if clicked.

Photo Credits, in order of appearance:

Thumbnail Image at beginning of article: Flickr Creative Commons, by mjambon, some rights reserved. The original may be viewed here.

Maps: the United States Department of Agriculture. Public domain.

Western Poison Oak: Dave's Garden Plant Files. Submitted by member Geoff Stein (PalmBob), and used with permisison. All rights reserved.

Eastern Poison Oak: Wikimedia Commons, by USDA photographer Robert H. Mohlenbrock. Public domain.

Poison Oak blossoms: Flickr Creative Commons, by randomtruth, some rights reserved.

Western Poison Oak berries: Flickr Creative Commons, by briweldon, some rights reserved.

Cluster of Poison Oak berries: Dave's Garden Plant Files. Submitted by member George Crozier (PotEmUp), and used with permission. All rights reserved.

Western Poison Oak, Fall Colors: Flickr Creative Commons, by ilya_ktsn, some rights reserved.